Hiller 360 - History and technical description

Some historical notes

The Hiller 360, also commonly known as the UH-12, was the first helicopter produced in series by the American Company United Helicopter Inc. of Palo Alto (California) founded by the rotary wing pioneer Stanley Hiller (1924-2006). This model was certified by the CAA to be produced in series on the 14th of October 1948 and obtained the CAA type certificate 6H1.

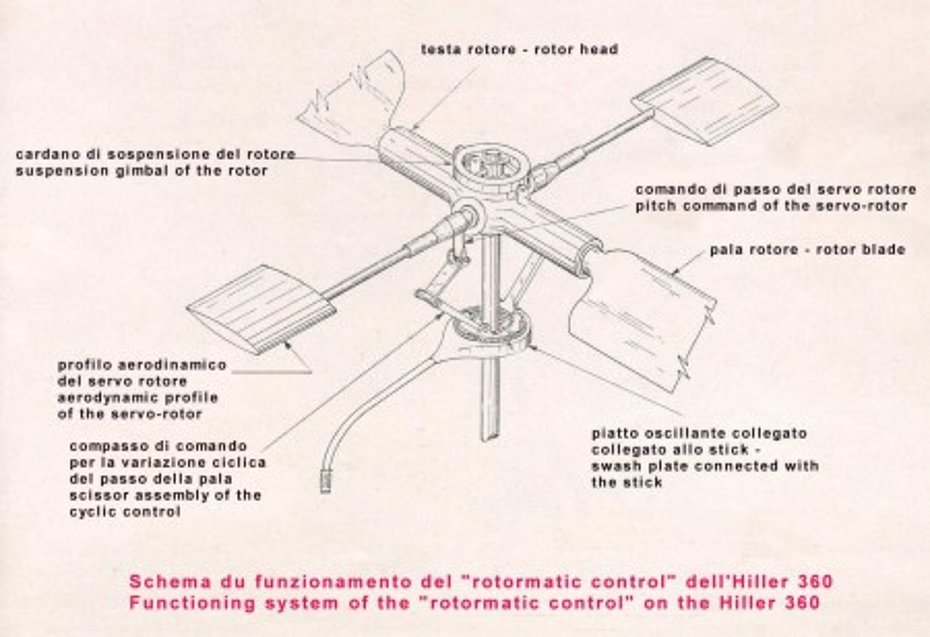

This helicopter differed from others for its innovative control system known as "Rotormatic" which is here shortly described. The servo rotor is connected directly through universally-mounted transfer bearing and simple linkage with the pilot's hanging control stick. Movement of the cyclic introduces to the servo rotor paddles positive or negative pitch changes and aerodynamic forces thus developed tilt the rotor head and produce the effect of cyclic pitch changes to the rotor blades. As it is showed in one of the pictures the inherent stability of this model is really remarkable.

The first pre-series models left the assembly line in March 1949, and the ones produced in series were available by the following month of May. The first was delivered on the 1st of March 1949 to B. F. Hodges of Walnut Grove (California) who used it to spray the crops in the Sacramento Valley.

The civil version was known as "Utility" while the "VIP" version, available from 1950, was designated “Executive”. At that time the direct competitor of the Hiller 360 was the Bell 47, which was available in the versions B, B3, D and D1.

In 1949 the Hiller 360 in the version "Utility" could be purchased for 19'995 US dollars and was the cheapest helicopter produced in series on the market. In Switzerland this model was marketed by the Air Import for about 175'000.-- Sfr.

Employ

In the civil field the Hiller 360 was primarely used for passengers transportation, aerial spray, the transport of mail, the observation and the photographic flights, as well as the aerial advertising.

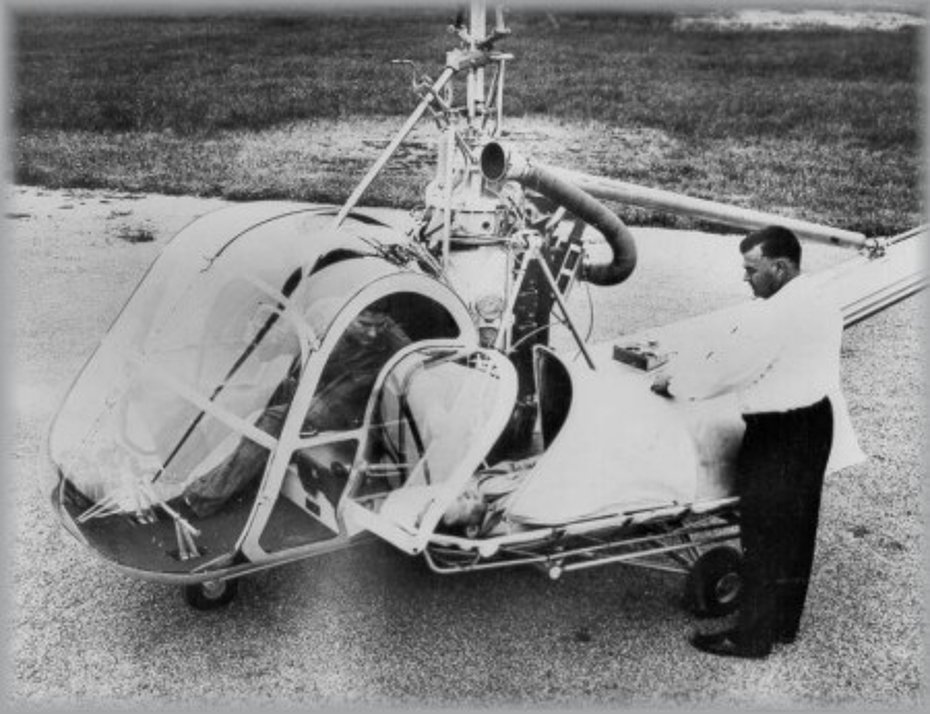

The Army also used it as an aerial ambulance (this version is known as the H-23A) especially during the Indochina and the Corea war. This helicopter could carry on each side of the fuselage a stretcher patient in a completely enclosed externally carried stretcher which was accessible from the cabin.

Technical characteristics

The Hiller 360 is a three place side-by-side helicopter with a two-blade main rotor. The main rotor blades (produced by the Parsons Industries Inc.) are of solid wood laminations. The body of the blade is in fact essentially made up of numerous strip and block wooden laminations designed to provide a strong but highly flexible blade. The entire blade surface is covered with fiberglas cloth with the leading edge and tip covered with an additional stainless steel sheet. The tail rotor is of all metal construction.

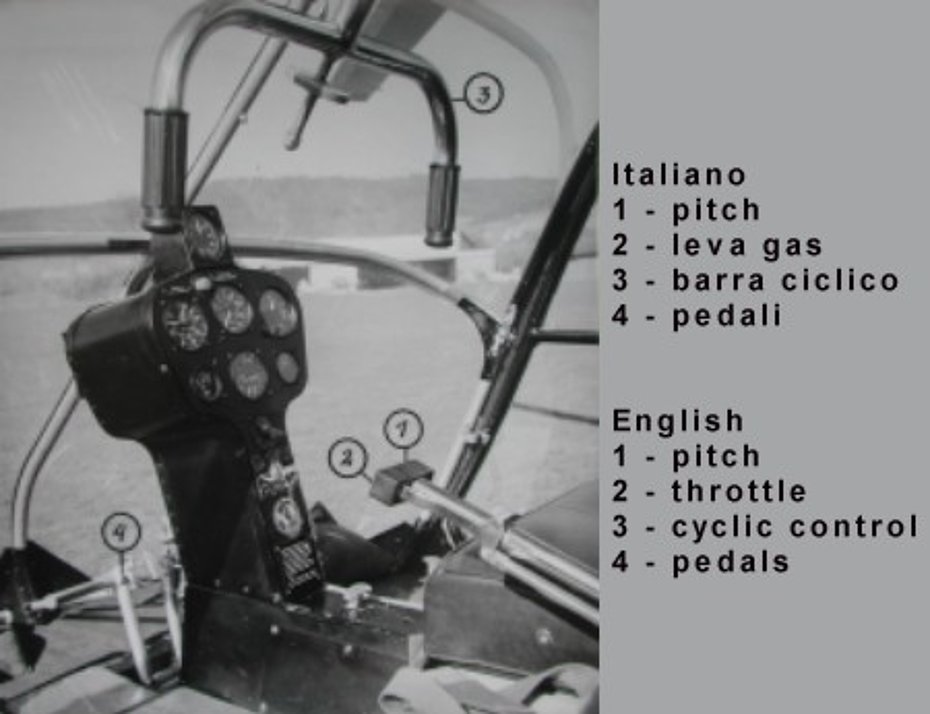

By virtue of the dual control arrangement the Hiller 360 may be flown from either the left or center seats depending on whether the pilot is flying solo or is carring one or two passengers.

When the pilot flyies from the left seat he must use his right arm to control the collective pitch lever, which is untypical on helicopters. The overhead cyclic bar incorporates a trim which is directly connected with a metal cable to the swashplate. Directional control is obtained with conventional type rudder pedals which vary the pitch change of the two blade metal tail rotor. There are two pairs of pedals, one placed centrally and one on the left side. The helicopter was usually delivered with a simple plexiglas windshield (to save weight and money), but when necessary there was also the possibility to enclose completely the cabin. The Hiller 360 was normally fitted with a tricycle landing gear, but could also be equipped with pontoons or skids. Originally it was powered by a six cilinders fan-cooled Franklin 6V4-178-B33 engine with a maximal power of 134/178 kW/hp at 3'000 rpm. The fuel system is relatively simple. There is a mechanical pump driven by the engine and a second electrically-driven auxiliary fuel pump. The tank haves a capacity of 102 litres (27 US gallons).

The automatic throttle is linked to the pitch control lever. There is a finger-tip lever for automatic override for final adjustment of the engine speed to most efficient rotor rpm and pitch setting for various loads und cruising speeds. Magneto, filters, generator, starter as well as others accessories are easily accessible. The maintance can be made without the use of special tools.

Equipment for crop-dusting, air-mail, cargo, photographic and survey operations could be easily installed without affecting its performance or flight characteristics.

Maintenance

A brochure published in 1949 indicates that the maintenance of the Hiller 360 could be easily made. The inspection after 25 respectively 50 hours of flight required 3 hours of work for a mechanic (without the engine controls). The 100 hours inspection required 20 hours. The general revision after 600 hours of flight required 300 hours.

Performances

With a total takeoff weight of 965 kg (1 pilot, 2 passengers, 100 litres of fuel, 10 litres of oil) the Hiller 360 haves a maximum cruising speed of 135 km/h and a standard cruising speed of 122 km/h. The maximum rate of climb is 220 m/min. At the MTOW of 1'020 kg the helicopter has a service ceiling of 3'100 m and can hoover in ground effect up to 1'450 m, while its range is 250-300 km.

Dimensions, weights and loadings

The Hiller 360 has a main rotor with a diameter of 10.67 m, and a tail rotor with a diameter of 1.67 m. The semi-monocoque fuselage has a total lenght of 8.08 m. Its maximal height is 2.89 m.

The empty weight of the helicopter equipped with a tricycle landing gear is 657 kg. In the original version the maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) is 1'020 kg. Deduced the standard weight of the pilot 77 kg and the reserve of fuel and oil for one hours of flight (36 kg) the payload is 247 kg.

Autorotation

The autorotation characteristics are the following. At the MTOW the aircraft descends power off with a rate of 600 m/min, or 10 m/sec. With a translational speed of 80 km/h the descent rate is reduced to 300 m/min (5 m/sec), with a descend angle of 13 degrees. In the flare phase the speed is reduced to 20-25 km/h. During this manoeuvre the rotor rpm must be kept between 294 and 350 rpm.

The Hiller 360 in Switzerland

The Hiller 360 HB-XAI (s/n 120 – b/y 1949) was the first civil helicopter to be registered in Switzerland. It was an occasion aircraft before registered in the United States (where it flew with the registration N8120H) bought by the Air Import of Lucerne for about 120'000 Sfr.

The technical control of the FOCA was made on the 12th of August 1949 on the aviation field of Biersfelden. From that date on the helicopter was used for the first flying demonstrations piloted by Albert Villard. On the 17th of November 1949 the HB-XAI became the first helicopter to perform a roof-landing. It landed in fact on the roof of the Jelmoli store in Zürich. On the 6th of January 1950, during the celebration of the Epiphany (the Italian counterpart of Santa Claus), it was presented in Milan. This was the first time that a helicopter landed in the Cathedral Square in the centre of the city and large crowds (several dozens thousands) were assembled to witness the event.

The HB-XAI flew in Switzerland for a short time. In September of 1950 it was in fact sold to the Italian helicopter company ELA (Elicottero Lavoro Aereo) based in Milan and it was egistered as I-ELAM.

In the short period of service in Switzerland it was primarely used for flight demonstrations, passengers flights and the training of the early Swiss pilots.

HAB 04/2010