Sikorsky S-58 - History and technical description

Origins and development

The Sikorsky S-58/H-34 was the last helicopter manufactured by Sikorsky to be powered by a radial engine and, along with the S-55 and S-56, another Sikorsky's winning horse of the 1950s.

In the post-war period, with the beginning of the so-called "Cold War", submarines were the main units of the fearsome Soviet Navy, which came to deploy the largest fleet in the world. The US Navy saw the serious threat and immediately ran for cover.

At the end of the 1940's the few models in service with the US Navy (Piasecki HRP Rescuer, Piasecki HRP and Sikorsky HO4S) proved to be unsuitable to be used as anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft mainly because of their limited payload and range. During the trials conducted in south Florida the engines overheated during prolonged hovers in the high heat and humidity necessary for sonar immersion. In addition to this, the operations at sea put a strain on the endurance of the structures, coatings and instrumentation.

However, in spite of the problems emerged, the experiences gained showed that the helicopter had considerable potential in this role.

In January 1950 the US Navy launched a competition for the supply of an ASW helicopter designed specifically for this task. The following June Bell, with the design of the Model 61, was awarded the contract which initially foresaw the construction of three prototypes, the first of which made its first flight with the famous test pilots Floyd Carlson and Joe Dunne at the Amon Carter Field (then Greater Southwest International Airport) on March 4, 1953 with the designation Bell XHSL-1 (X - Experimental) (H - Helicopter) (S - anti-Submarine) (L - Bell).

The XHSL-1 was chosen because the US Navy, on the basis of the experience with the Piasecki HRP, was convinced that the tandem design offered more advantages.

A series of delays due to various problems (at the head of these there were the strong vibrations of the rotors) afflicted the XHSL-1 which by the end disappointed the expectations. The noise generated by the rotors for example disturbed the activities of sonar operators, the folding of the blades was laborious and because of its large size the aircraft barely fit in the lifts of ships. Only 53 units were manufactured.

Mors tua vita mea

While the Bell HSL-1 was being tested, Sikorsky undertook the development of the Sikorsky S-58, which, according to the information gathered in the archives of the American manufacturer, was initially financed with company's own funds.

Apparently, this program was less ambitious than that of the S-55 as it was a development of an already existing helicopter. In order to overcome the above-mentioned shortcomings (limited payload and reduced range) the designers developed a new aircraft which maintained the general layout of the S-55, i.e. with the engine mounted in front, overhead pilot's cabin and large cabin cargo volume.

In June 1952 the US Navy commissioned Sikorsky to build four S-58 under the designation XHSS-1.

Compared to its predecessor the S-58 had a larger payload capacity, an engine with more than twice the power, a new four-blade main and tail rotor, a more aerodynamic fuselage, a new tail section which sloped downwards and partially folded to reduce the size of the aircraft and a tricycle landing gear.

The prototype of the Sikorsky S-58 made its first flight on March 8, 1954, piloted by Dimitry D. (Jimmy) Viner (1908-1997) grandson of Igor I. Sikorsky and Sikorsky’s first test pilot.

The tests conducted by the US Navy were successful and the first order was placed under the new designation HSS-1 Seabat (the name comes from a species of starfish of the Asterinidae family).

The first HSS-1 (later designated SH-34G) which was the US Navy's basic version flew on September 20, 1954 while the deliveries for evaluation to the Naval Air Development Squadron (VX-1) then based in Key West/Florida begun in August 1955.

The problems related to the use of the Bell HSL-1 and its premature bow out obviously played in favour of Sikorsky.

The success of the S-58 was mainly due to some technical innovations (for example the use of flight controls equipped with irreversible hydraulic servos, already adopted as standard on the S-55) as well as the adoption of an effective electronic system of flight stabilization, which was able to lighten considerably the work of the pilots especially in difficult flight conditions.

The development of the Automatic Stabilization Equipment (ASE) was an outstanding engineering achievement, earning Assistant Chief Dynamics Engineer Ted Carter the Gold Medal and the George Mead Award given annually by the United Aircraft Corporation for outstanding engineering achievement (first presented that year), while Silver Medals and other awards were given to Harold S. Oakes, Jr., Assistant Chief Avionics Officer, and Henry R. Angel (Hydraulics Specialist) and Test Pilot Jack Stultz, also of Avionics, for the development of the helicopter's instrumentation.

The ASE allowed the helicopter to approach the sea surface and maintain a fixed-point position for sonar use without pilot assistance.

The SH-34J version developed specifically for ASW use featured an automatic engine speed governor, a Ryan C.W. radar navigator. Doppler radar navigator, an AN/AQS-4/-5 submersible sonar and the ASE, which, as said, was a huge step forward for anti-submarine warfare, allowing missions at night and in low visibility conditions. The SH-34J could carry 2 torpedoes, 2 mines or 2 depth charges. To increase the range it could be equipped with additional tanks that could be dropped in flight.

The US Army also discovered the qualities of the new aircraft and after extensive testing in the summer of 1955, it placed its first orders. The US Army named it H-34 Choctaw, a traditional name in honour of a Native American population from the South of the United States of America, and the Marine Corps named it HUS-1 Seahorse.

The orders from the Army, US Coast Guard, US Marine and US Navy for hundreds of aircraft forced Sikorsky to work at full capacity in its Bridgeport headquarters, now dedicated almost exclusively to the production of this aircraft.

To meet all commitments, the number of employees increased from 5,328 in 1955 to 10,653 in 1958.

At that period the waiting time for the delivery of a new helicopter was almost one year. An average of one helicopter per day came off the assembly line. The mass production of other models was started in the new factory of Stratford, only a few kilometres away.

In November 1958, the 1,000th model was assembled at the Bridgeport plant. The event was celebrated with a ceremony to mark the important milestone.

In the course of production, modifications were introduced which in some cases led to the creation of a variant designed for a specific use. The S-58C for example has a reinforced cabin floor. Even models of the same version could differ from each other.

Among the minor modifications was the engine exhaust. The flames coming out of the exhaust pipe disturbed pilots flying at night. The solution proposed by the manufacturer was the so-called "high-stack flames-dampening-exhaust".

The bottom-mounted exhaust pipe posed a problem when the helicopter was equipped with floats, therefore a special exhaust with only one exhaust pipe was mounted on these models mostly used for off-shore operations. The landing gear was also modified. All variants were quite similar to each other.

In June 1962 Sikorsky produced its 1,500th model and still had numerous orders in progress. Starting from that year, however, its formidable successor, the SH-3 Sea King, began its very long operational career.

On April 15, 1963, the fleet of 1,614 S-58s produced to date had accumulated 1,684,695 flight hours.

According to the magazine "Sikorsky News" the production in series was suspended for the first time in October 1964 when what was then believed to be the last model came off the assembly line with the affectionate writing on the fuselage "Good-bye, old friend". At that time the S-58 fleet in service had accumulated a total of 2.5 million flight hours.

In the following months, however, new orders accumulated and therefore the assembly line was restored.

It is difficult to establish the exact number of units produced by Sikorsky.

Several sources indicate a total of 1,821 aircraft the last of which left the factory in January 1969.

In June 1955 the basic model of the S-58 with standard equipment cost $248'000, the equivalent of about 1'318'500 CHF (today about 4'360'000 CHF).

None of the helicopters in service with the US Navy sank Russian submarines, but Sikorsky's helicopters were used in various theatres of war (e.g. Algeria, Cuba crisis, Vietnam).

The appearance of new helicopters conceived from the beginning to be powered by a turbine such as the Bell 204/205 (UH-1 Huey) made the S-58, which represented in a certain sense the apex of the evolution of medium transport helicopters with piston engines, soon obsolete.

After the failure of the unfortunate Bell HSL-1 Bell took its revenge on its historical competitor.

Increasingly rare sightings

The replacement of the radial engine with a turbine greatly extended the operational life of the Sikorsky S-58 which was the last helicopter manufactured by Sikorsky to be powered by a piston engine and together with the S-55 was the first American helicopter mass produced for military troop transport.

Despite the fact that it was manufactured in large number, today most of the surviving models can be found in warehouses all over the United States and in museums.

In Europe apparently the only flying model is the S-58C D-HAUG of Meravo-Luftreederei GmbH based in Oedheim bei Heilbronn (about 45 km N of Stuttgart). It can be seen at aviation meeting and has also taken part in some films.

(web - ADF Helicopters)

In the United States some operators still use the S-58 for commercial transport. They are occasionally used for lifting air conditioners onto roofs.

ADF Helicopters based in Brewster, Washington, operates a fleet of Sikorsky S-58s to protect cherry crops from damage.

Turbine conversions and production in series

The appearance of the first turbines specifically developed to be used on helicopters pushed the manufacturers to consider this promising alternative to make their models even more performing.

Sikorsky experimentally developed a prototype that made its first flight on January 30, 1957, known as the HSS-1F with two General Electric T58 engines instead of the R-1820.

The Sikorsky S-58 was produced under license in France by Sud Aviation and in the UK by Westland Helicopters. The French manufacturer assembled about ninety aircraft with parts supplied by Sikorsky, then manufactured 185 (other sources indicate 166) for the French and Belgian navies (HSS-1) and the French Air Force (HUS-1 variant).

On October 5, 1962, Sud Aviation completed the first flight of the S-58 version in which two Turboméca Bastan IV engines replaced the original Wright Cycone radial engine.

Westland Helicopters chose to develop and build a turbine-powered helicopter on the S-58 airframe; the first Westland Wessex HAS.1 for the Royal Navy fitted with a Napier Gazelle turboshaft flew for the first time on June 20, 1958.

Westland built a total of 356 Wessex helicopters in different variants.

Commercial employment of the S-58

It did not take long before civilian operators started to show their interest for the S-58 and therefore in July 1955 Sikorsky started to collect the first orders, giving priority to the supply of the US armed forces.

The commercial certification of the S-58C was obtained on August 2, 1956.

This version was specifically designed for scheduled passenger transport and had two doors on the starboard side. It could carry twelve passengers in four rows of triple seats arranged in a mirror pattern.

On October 19, 1955 during a press conference New York Airways announced the purchase of 7 S-58s, the first of which was to enter service on June 15, 1956.

The first three aircraft, which together with the spare parts involved an investment of 1,2 million USD, did not enter into service until the end of the year.

Among the first customers there was the Belgian company Sabena which purchased 8 S-58C. The first (s/n 58-356) arrived in Belgium on November 7, 1956 and received call sign OO-SHI on November 26, 1956.

Another operator of that period was Chicago Helicopter Airways.

The S-58B was the general-purpose civil variant, with a foldable bench for five to seven passengers and provision for carrying cargo. The maximum take-off weight was increased from 12,700 lbs (5,760 kg) to 13,000 lbs (5,897 kg). This increase was made possible by the modification of the new carburettor air duct and the new design of the engine-cooling fan which absorbed less power so that the engine supplied about 36.7/50 kW/hp more to the transmission.

In the civilian variants, the engine was designated Wright Cyclone 989C9H2-2 or 998C9HE-2.

The Sikorsky S-58 was widely used in the period ranging from the second half of the 1950s and the end of the 1970s.

In addition to scheduled passenger transport (for various reasons - first and foremost the appearance of more modern twin-engine models such as the Boeing-Vertol 107 and the Sikorsky S-61 - its use in this role was relatively short) it was used by oil companies for the transportation of personnel, supplies and material on oil rigs. It was also employed to transport construction materials and assemble prefabricated structures.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Department employed some S-58s in the 1970s and early 1980s mainly for search and rescue, aerial surveillance, ground patrol support and personnel transport.

The tragedy of Forest Park

The brilliant career of the Sikorsky S-58 ran the risk of being overshadowed by a terrible accident that occurred on July 27, 1960 in Forest Park, Illinois. That evening the aircraft registered N879 in service with Chicago Helicopter Airways on an 11-minute connecting flight between Chicago Midway Airport and O'Hare Airport crashed and burst into flames at Forest Home Cemetery causing the death of all eleven passengers and two crew members.

The Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) immediately opened an investigation to clarify the cause of the accident. From the beginning there was the suspect that the cause of the accident was the breakage of a main rotor blade which was found on top of a tree 3/4 of a mile from the point where the main cabin section crashed.

FAA ordered to ground all aircraft whose blades had more than 500 hours of service. It also requested daily inspections and checks on the blades that were originally designed to have an operational life of 2,450 hours.

On August 3, 1960, the FAA issued an airworthiness directive setting inspection requirements for the main rotor blades and limiting their service life to 1,000 hours.

At the end of the investigation FAA's committee established that the accident was initially caused by a fatigue failure of the metal of the blade which after having fractured separated causing the partial disintegration of the helicopter in flight.

Fuselage

As previously mentioned the S-58 was designed with ease of maintenance in mind. On all variants the engine is protected by non-structural clamshell doors which provide access to the engine and accessories from ground level with variation in the port door for the three different exhaust configuration.

The wind tunnel developed aerodynamic airframe is an all-metal, semi-monocoque structure primarily of magnesium and aluminium alloys, with some titanium and stainless steel parts.

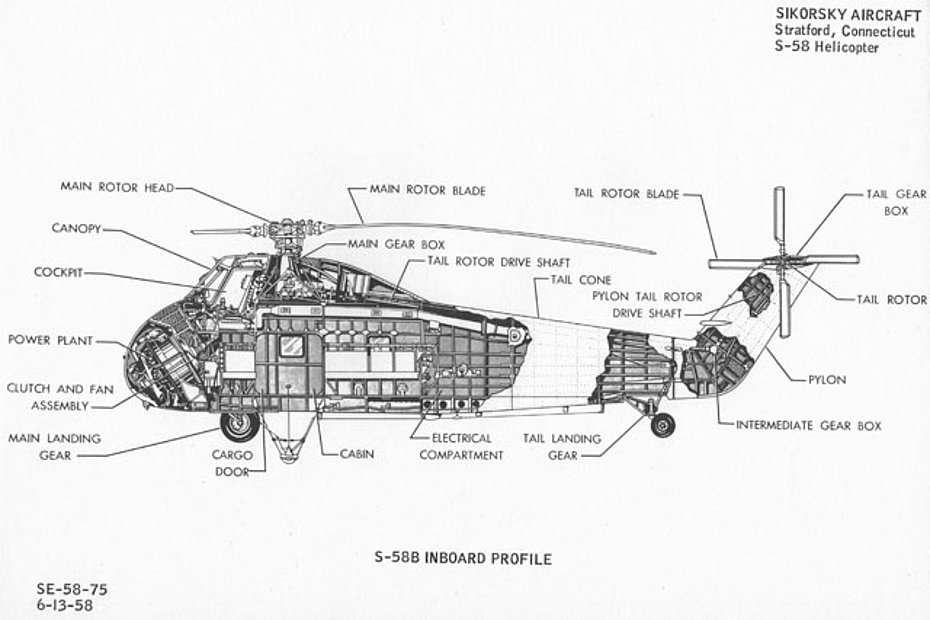

The main sections are a forward engine compartment, a cockpit above and behind the engine, a transmission deck behind the cockpit, a main cabin box below the transmission deck and behind the engine and a downward-sloping tail section that includes the tail rotor pylon.

The fuselage is skinned largely with magnesium (corrosion and the fire hazard experienced with certain S-58 models discouraged further use of magnesium for airframe components by Sikorsky on subsequent models).

Pilot's compartment above main cabin seats two side by side with dual controls. Access to either side of the cockpit is typically gained by way of kicksteps on the forward fuselage, with the large sliding side windows (removable in case of emergency) providing room for entry. The windows were at the beginning flat, then bulged to improve the pilot’s visual.

The pilots jokingly affirm that if you can board the S-58 then you can also fly it!

It is also possible, even if it is cramped and ankward, to pass between the cockpit and the passenger-cargo compartment. This is done by raisin the bottom pan of the pilot’s or co-pilot’s seat and crawling through the resulting gap between the rear cockpit bulkhead and the floor.

Entry to the passenger-cargo compartment is easier, with a large, aft-sliding door on the starboard side. This presents a 90 cm sill, however, which might be ideal for loading and unloading cargo but provided a challenge for combat-laden troops. For this reason various step configuration were developed.

The bottom structure was originally made of magnesium then aluminium. The S-58C has a stronger structure made of aluminium with stainless steel keel beam. Fuel dump pipes run along the fuselage bottom under protective covers.

Passenger’s cabin and cockpit are heated and soundproofed.

The S-58C is the only version with a baggage compartment. On this version the radio equipment was originally located above this compartment (on all others version it was located aft of the cabin between stations 246 and 296), and partitioned by a removable, zipper-closure curtain.

Standard equipment included structural provisions for a cargo sling. On this regard there are two models. The original 4,000 lbs (1,814 kg) Manning-Maxwell and More was replaced by 1956 with the Eastern Rotorcraft A-60 model with a load capacity of 5,000 lbs (2,269 kg).

The hydraulic winch has a 272 kg (600 pounds) lift capacity. Optional equipment included 30 meters (100 ft) or 90 meters (300 ft) of rescue cable.

The main rotor is driven by a transmission connected to the engine by a shaft running from the clutch compartment through the forward cabin bulkhead, the forward cabin and the main transmission deck. Shafts and gearboxes running internally along the spine of the tailboom and rotor pylon provided power for the tail rotor.

In the rear of the fuselage there is a horizontal stabilizer made of magnesium skin over magnesium and aluminium structure.

To meet Navy’s requirements for compact shipboard stowage the tail pylon is hinged so that it can be manually folded laterally to the left against the fuselage allowing the helicopter to fit on aircraft carrier elevators. By doing this the full length is reduced to about 12.30 m (37ft), in addition the main rotor blades can also be folded.

After being sold to civilian operators, many ex-military aircraft were modified. For example, new windows were added and the access door to the passenger compartment was widened, new cabin step were fitted.

Rotors

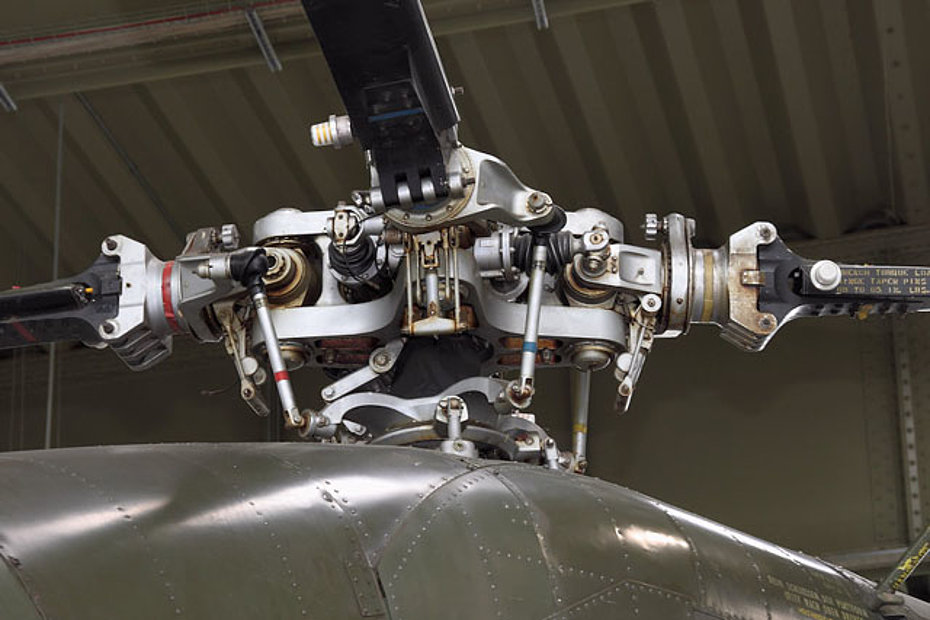

The Sikorsky S-58 has a fully articulated four blades main rotor.

Each main rotor blade is made of a hollow extruded aluminium spar and trailing edge pockets of aluminium. Each tail rotor blade has an aluminium spar, sheet aluminium skin and honeycomb trailing edge. Blades of each rotor are interchangeable. The blades were designed for durability, and were immune to high umidity and temperature.

Both main and tail rotor blades use the symmetrical NACA 0012 airfoil. Sikorsky chose a 4-blade rotor for the S-58 because it produced a lower blade loading compared to the 3-blade S-55 rotor. Another reason for the four blades was to reduce aircraft vibrations.

Main rotor blades were identical on all models. In November 1956 a heavier spar was introduced on the H-34A and the commercial version which made their apparition in that period. On US Navy and Marines model the modification was introduced in January 1957.

Despite author's research it has not been possible to establish whether additional safety measures were adopted after the tragic accident July 21, 1960.

We are talking about the BIM (acronym for Blade Inspection Method), an indicator mounted at the blade root end that changes color if the spar develops the smallest crack thereby releasing the internal 10 psi pressurized nitrogen which activates the indicator position and a visible color change.

The BIM system provided a major improvement to flight safety. It was first used on the S-58 main rotor blades and then offered to S-55 operators.

All blades were balanced and tabbed on the main rotor blade whirl stand against a master blade and stencilled with the required adjustment on installation. This eliminated the requirement to manually track blades when installing a replacement blade.

Flight controls

Dual flight controls and a consolle between the pilot’s seats allow either pilot to operate all controls and the radio. Flying controls are fully powered in duplicate without manual reversion, separate hydraulic systems being driven by pumps on the engine and rotor transmission respectively. It is normal pre-flight test procedure to switch off the systems one after the other before take-off, to check that they are both working, but Sikorsky have made it impossible to cut one system if the other is not already operating.

The tail rotor is powered but is restrained by a hydraulic damper so that directional control can be applied only very slowly. This is intended to prevent pilots snapping from full rudder one way to full rudder the other, and thereby overstressing the fuselage.

All the systems are controlled from a central rectangular panel beneath the engine instruments. Radio panels and the various levers for engine control, mixture, carburettor heat, intake filter and so on, are on the central consolle, which extends from the main panel right back between the seats. Piloting action is simplified by a spring-loaded, stick-centering device which provides a stick-stabilizing tendency for any set flight condition.

Many of the controls are mounted on small panels at the tip of the collective lever or on the hand-grip of the cyclic stick.

Large pilot seat enhance comfort and reduce fatigue.

Transmission

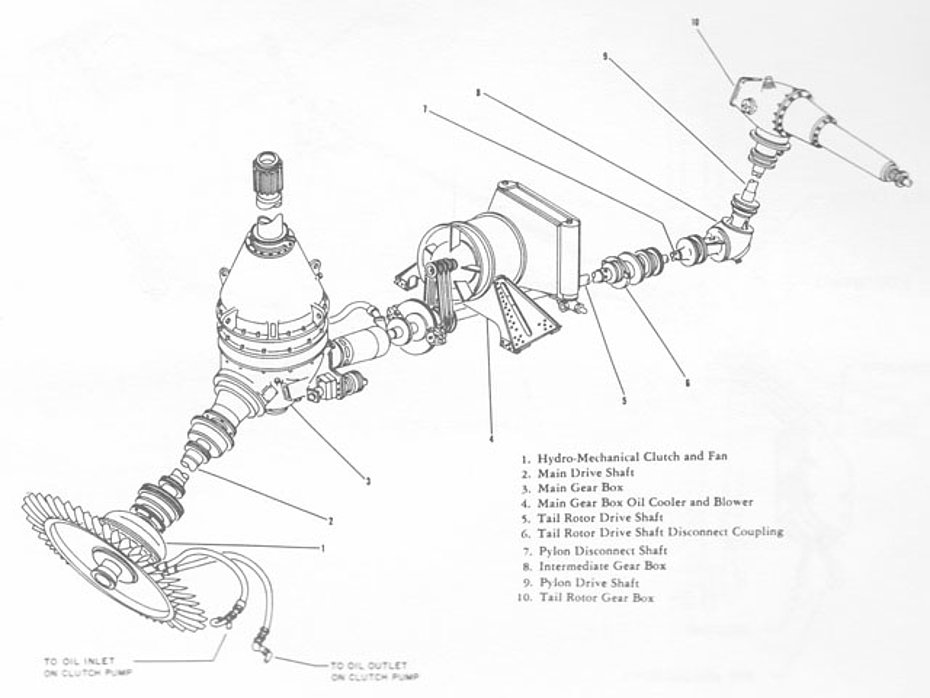

The main gearbox in the transmission system is mounted above the cabin. The gearbox contains bevel gears and a single-stage planetary gear system which reduce engine to rotor rpm at a ratio of 11.293 to 1 for driving the main rotor. Additional shafting extends from the main gearbox lower housing through the intermediate gearbox and tail rotor gearbox to drive the tail rotor (engine to tail rotor ratio 1.884 to 1) located on the top of the tail pylon.

Most of the critical structural or transmission components of the S-58 owe much to experience gained with the S-55, and in some cases the S-58 has a directly scaled-up S-55 part.

However, the S-58s transmission system has 25% fewer parts than earlier Sikorsky designs, and provides accessory drives for the generator and its cooling blower, the primary servo-control hydraulic pump and the hoist, rotor tachometer and hydraulic clutch.

Power is transmitted to the rotors by means of the hydro-mechanical clutch located between the engine and the main drive shaft. An electric pump, located on top of the left engine oil tank, pumps oil from the tank beneath it into the fluid coupling housing to provide the medium through which engine torque is gradually transmitted to the transmission drive shaft. The pump operates on direct current from the primary bus.

The lower end of the clutch is splined to the engine shaft and the upper end is bolted to a rubber coupling at the lower end of the drive shaft of the main gear box. The clutch consists of a fluid coupling and a mechanical coupling incorporating a freewheeling unit. The functions of the fluid coupling are to permit the engine to be started and operated while completely disengaged from the transmission and rotor systems, and to provide a smooth acceleration of the transmission and rotor systems at the time of clutch engagement.

The freewheeling unit eliminates drag during autorotation by automatically disengaging when engine speed falls below the equivalent main rotor speed.

Standard equipment includes a warning light system that indicates the presence of metallic fragments in the sump of the main, intermediate and tail gearboxes and the engine.

Flight instruments

Instruments are located in front of the pilot. Access to the instruments is provided by a removable fairing at the top of the panel. The main switch panel, located in the center of the instrument panel, is illuminated by red edge lights and hinged for wiring purposes.

The overhead switch panel, circuit breaker and fuse panel, rotor brake and light are mounted between the cockpit seatback.

All military models had instrument panels with similarity of function but there were variations in grouping the instruments.

The standard commercial instrument panel provided for optional gyro and co-pilot units in addition to the pilot’s basic grouping.

Landing light controls are also provided.

Engine

Power for the main and tail rotor is provided by the nose-mounted single-row Wright R-1820-84 Cyclone engine. The 9 cylinders radial engine (29,880 litres or 105.52 cu ft) is cooled by screened air intakes around the nose and a fan mounted behind the engine.

For all military models the Wright R-1820-84 Cyclone series was standard. The commercial and export equivalent was the Wright 989C9HE-2. The original military models were the -84A (Army) and -84B (Navy and Marines). Heavy-duty pistons were incorporated and the engines became -84C and -84D respectively.

The powerplant which weights 634 kg (1,398 lb) is mounted at a 34 degree forward angle with the shaft facing aft.

The engine installation angle was chosen to permit its drive shaft to travel up between the pilots and enter the main transmission at the optimum location.

Military S-58s mounted a titanium firewall to separate the engine compartment from the cabin, while commercial models had a stainless steel firewall.

At sea level the engine develops a take-off power (limited to 5 minutes) of 1,137/1,525 kW/hp at 2,800 rpm and 57.5 PSI (250 rotor RPM). In cruise flight maximum power is 671/900 kW/hp at 2,500 rpm giving 220 rotor RPM.

In cruise flight normal fuel consumption is about 335 litres/h (88 USG/h).

The commercial models have fire sensors in the engine and heater compartment, while only the H-34A and VIP variants have sensors located in the engine compartment.

A brochure dated October 1962 indicated that the Wright Cyclone R-1820 engine TBO was 500 hours.

Fuel tanks

The S-58 is equipped with three interconnected fuel tanks installed in compartments under the cargo cabin floor.

Depending on the version, the amount of neoprene impregnated nylon cells changes as for the amount of fuel carried.

On the HSS-1 and HUS-1G the front compartment consists of five cells for a total of 115 USG (435 litres). On the other models five self-sealing cells (a protection in case of attack with light arms) for a total of 100 USG (378 litres). The commercial models has a five-cell front tank totalling (123 USG) 465 litres.

The central tank consists of three cells totalling 267 litres (70.7 USG).

The rear tank, optional on commercial versions, has a fuel capacity of 92.3 USG (349 litres) in three cells.

The filler cap is located on the right side of the fuselage.

If necessary, the auxiliary fuel was carried into the cabin and transferred during the flight by gravity.

In the past the engine was powered by Avgas 100/130 octane gasoline, while nowadays those left in service use Avgas 100LL.

Electrical system

The helicopter has a 24V DC (36V was optional) electrical system. On commercial models, a 300 ampères generator (driven by the engine) and wiring are fitted to power all standard and optional equipment (except electronics). Military versions used various types of generators 300 or 400 ampères mounted on both the transmission and engine.

Maintenance

The S-58 was designed with ease of maintenance in mind. Simplified access to all components is a key feature.

According to the information contained in the advertising brochures, it takes 3 mechanics 3 hours to replace the rotor head and main transmission, while it takes 2 mechanics 2 hours to replace the tail rotor transmission.

The main transmission is accessible by hinged panels which open quickly to provide service platforms. Other panels give complete access to servo units, flight controls, and the accessory section of the main transmission. Hinged clamshell doors expose the entire engine, the clutch and the accessories and allow complete accessibility from ground level for inspection and service purposes.

Landing gear

The S-58 employs a conventional three-wheel undercarriage, with drag struts hinged to rotate about a transverse axis, the vertical loads being taken by long oleo-pneumatic shock-struts attached to one of the main upper longerons on each side.

The original landing gear nicknamed “bent leg” because of its shape, was prone to structural failure and inducing ground resonance.

Sikorsky then introduced the model with two horizontal struts positioned in a V-shape. However, as the modification of the original model was extremely time-consuming (and therefore expensive), only in very few cases the landing gear was modified.

The hydraulic mainwheel brakes are toe operated.

Tailwheel is fully castoring (and enhances ground handling by greatly reducing the turning radius of the helicopter) and self-centring, with an anti-swivelling lock. The rear tail wheel also improves safety in a quick stop. Mainwheel tyres 11.00 x 12. Tailwheel tyre 6.00 x 6. Track 3.66m. Wheelbase 8.75m.

Accessories

The S-58 could be equipped with a long list of accessories which included for example: radio, additional instruments for the co-pilot, autopilot, foldable troop type seats for 12 occupants, provisions for stretcher, rescue hoist, cargo sling, landing lights, 36 Ah battery (instead of 25), internal rear tank, anti-collision light system, emergency floats, fixed floats, soundproofing in the cabin for pilots and passengers, heating, VIP interiors, additional windows.

Weights and dimensions

The main rotor of the Sikorsky S-58 has diameter of 17.07 m (56 ft) while the rotor disc has a surface area of 228.81 sq m (2,463 sq ft), and the tail rotor has a diameter of 2.84 m (9 ft 6 in) and a disc surface area of 6.59 sq m (70.88 sq ft).

The fuselage is 14.25 m (46 ft 9 in) long, while the height measured at the mast is 4.36 m (14 ft 3.5 in).

The cabin has the following interior dimensions: total length 3.91 m (12 ft 10 in), maximum width 1.52 (5 ft), maximum height 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) floor area 6.04 sq m (65 sq ft), volume 9.91 cu ft (350 cu ft).

The empty weight of the aircraft obviously changes depending on the optional equipment installed.

The standard empty weight is 3,754 kg (8,275 lb), while the maximum take-off weight is 5,900 kg (13,000 lb) with internal load, respectively 6,350 kg (14,000 lb) with external load.

The payload is 2,143 kg (4,725 lb), but it is reduced to 1,395 kg (3',075 lb) with a full fuel load.

The structural limit of the cargo sling is 2,269 kg (5,000 lb).

The Sikorsky S-58 in Switzerland

The Sikorsky S-58 probably made its first appearance in Switzerland on December 11, 1957. On that day in Belp/BE the military pilot Hansueli Weber had the opportunity to carry out some flight tests on behalf of the Military technical division and wrote a short report.

On November 16, 1958, the Sikorsky S-58B registered N421A piloted by Jack Keating landed in Lugano-Agno/TI.

This helicopter was used to carry out an experimental connecting flight in view of the establishment of an air taxi service to transport passengers between Milan and Lugano/TI.

The optional equipment installed on the N421A included the ASE, a special device for towing demonstrations both on water and on land, the rescue hoist, a cargo sling with a maximum payload of 2,041 kg (4,500 lbs), full instrumentation for pilot and co-pilot and a tethering coupler which permitted a ground operator to maneuver the aircraft after the pilot has come to a hover and punched the prooper button on the ASE. Another modification to the S-58B was a single window in the cabin door, giving greater visibility.

In 1960, starting from the beginning of May, the Italian company Elipadana rented from Sabena two Sikorsky S-58C for a shuttle service between Milan and Lugano. At the end of July the director of the Italian company informed the Swiss Federal Aviation Office by telex of his decision to suspend definitely the shuttle service mainly because of the lack of passengers and other problems related with the managment of the heliport in Milan.

The employment of the Sikorsky S-58 in the Swiss Alps

In July 1962 the Sikorsky S-58C F-OBON in service with the French company Gyrafrance was used on several occasions in the Swiss Alps on behalf of Heliswiss. Piloted by Claude Aubé (1932-2013) it was used to transport building material for the construction of a power line in Engadine/GR. Loads weighing 350-400 kg were airlifted up to 3,000 meters (9,845 ft).

More or less at the same period it was employed in the region of Robei (Canton Ticino) where works for the construction of a new powerline were underway and in the Bernese Oberland were the construction of the Stechelberg - Gimmelwald - Mürren - Birg cableway were started by the Schilthornbahn AG founded in 1962.

As the former head of the Heliswiss technical service Ruedi Renggli remembers "After its arrival the S-58 was left in the open air in Mürren overnight. I still remember very well that the next morning, in order to start the Wright Cyclone engine, the French mechanic, using a small hammer, began to tap the engine’s valves, which presumably liked to seize when they were cold. For a moment we thought he was playing a xylophone, then finally the huge radial engine after a few loud bangs started, but it took a while before it reached the required operating temperature. Finally the pilot gave the starting signal, but before starting the transports he made a reconnaissance flight, taking with him the mechanics and a Heliswiss flight attendant that he deposited in Birg. The Garaventa technicians showed with gestures where to place the loads. By the evening all flights were completed without any problems”.

According to Heliswiss’ annual report F-OBON did altogether 37 hours of flight in Switzerland in 1962.

The same aircraft was again called into action on at least two separate occasions for a delicate operation, namely the recovery of airplanes which had crashed in the Swiss Alps.

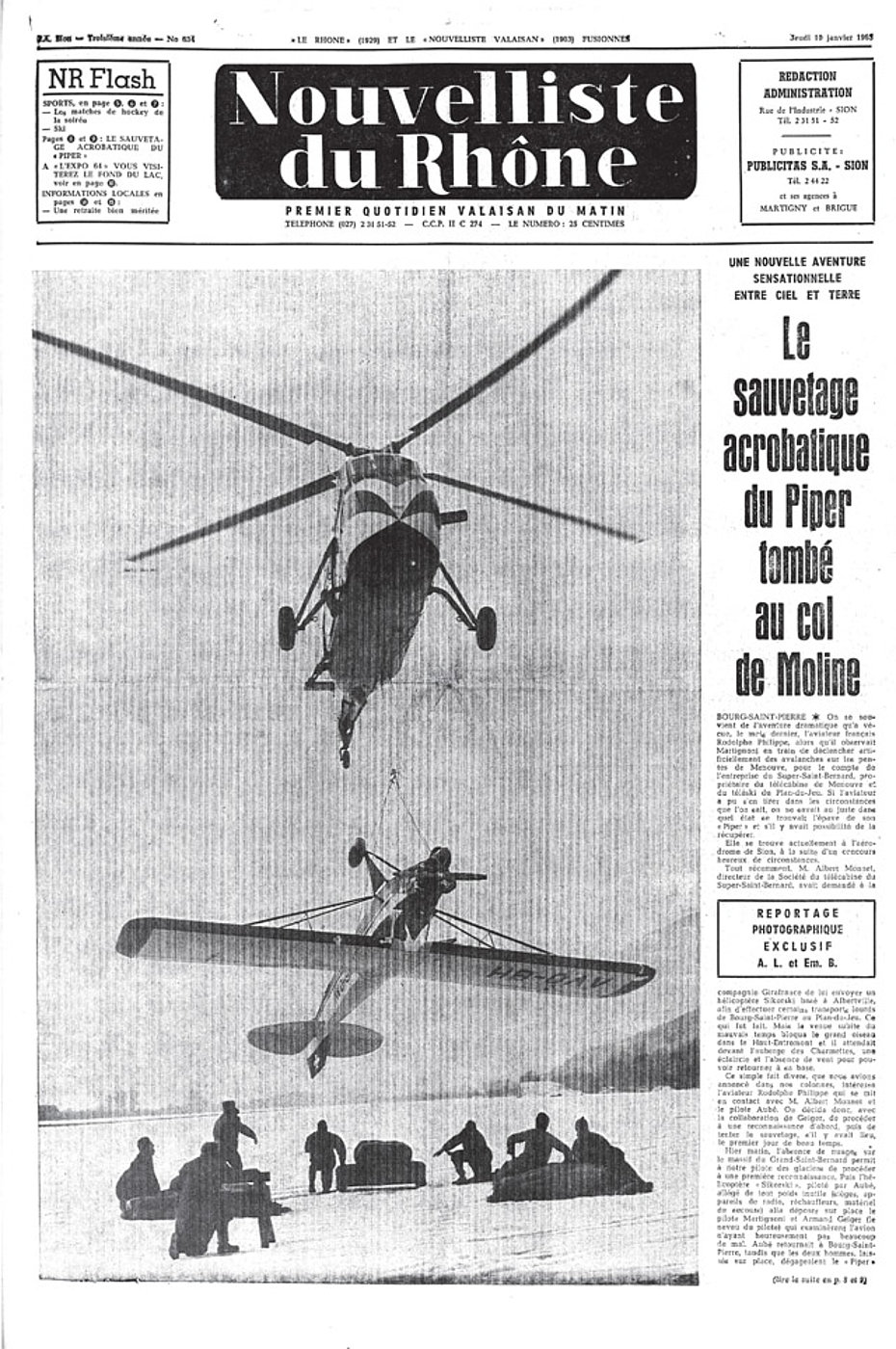

In January 1963 the aircraft piloted by Claude Aubé made several transports between Bourg-Saint-Pierre and Plan-du-Jeu (Valais). On January 9, 1963, taking advantage of the presence of the helicopter in Switzerland, the aviator Rodolphe Philippe with the help of the famous glacier pilots Hermann Geiger and Fernand Martignoni organized the recovery of the Piper L-4J HB-OAV of the AeCS Séction du Valais which had been damaged on December 17, 1962 after a crash landing at the "Col de Moline" at an altitude of 2,900 meters (9,517 ft) on the Great San Bernard massif.

Claude Aubé and Théo Meury in order to lighten the helicopter as much as possible disassembled the passengers seats, the radio equipment, the heating system components and the rescue equipment.

After having been freed from the snow the plane was hooked to the helicopter and like a prey in the claws of an eagle it was transported directly to the airport of Sion where a group of Aero Clubs took it over. The operation was a great success and made the front page of the Valais newspaper.

Glarus Alps - Un échec presque total 'An almost total failure'

The same cannot be said for a similar operation which involved the same helicopter (F-OBON) piloted this time by André Henri Voirin (1922-2010). On May 21-22, 1963, the French pilot was charged to recover two damaged airplanes in the Glarus Alps.

The Swiss Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau issued a report which gives us an insight into the events.

On May 9, 1963, the aircraft Champion 7 GCB HB-UAM was damaged during a landing on the Claridenpass. The next day the pilot (and future co-founder of Heli-Linth Hans Coppetti) at the controls of the Piper Super Cub HB-ORP went to the accident site in order to dismantle the aircraft. During the successive takeoff he damaged the aircraft.

Coppetti asked Heliswiss to recover the two aircraft and the latter took contact with Gyrafrance.

On Monday May 20 Voirin accompanied by co-pilot Jacques Petetin landed in Geneva. The next day the helicopter landed at Mollis/GL airport after a short stopover in Zurich. After having discussed the details of the mission the crew of the S-58C took off and headed towards the Claridepass where it landed at 10:17.

After having been cleared from the snow HB-ORP which was located on a steep slope at 2,840 m/sm (9,320 ft) was prepared to be airlifted. Cables were attached at four points. After starting up the aircraft Voirin with Petetin and a mechanic on board moved to the vertical for the docking maneuver. The airplane was slowly lifted from the ground but shortly after it began to swing and one of the wings hit the fuselage of the helicopter slightly damaging it. Feeling in danger the pilot released the plane that slipped down for about 150 meters before coming to rest. The crew decided to interrupt the rescue action and returned first to Mollis, then flew to Stans where the helicopter’s damages (about 500 CHF) were immediately repaired by Pilatus Flugzeugwerke AG.

Early the next day the French team flew again to Claridenfirn with the intent to recover the Champion 7 GCB HB-UAM which was located about 700 meters south of Planurahütte at an altitude of 2,945 meters (9,665 ft) on the Hüfifirn. The engine and the landing gear of the aeroplane were in the meantime removed. After the hooking manoeuvre the fuselage again started to rotate and swing but this time Voirin in 15 minutes managed to descend the precious cargo to Mollis. Unfortunately, instead of depositing it gently the pilot released it from a low altitude causing further damages to the already battered aircraft.

The helicopter took off again towards Claridenpass to recover HB-ORP which had been also partially dismantled. The engine together with other small components were carried by the S-58 into a net at a point from where they were descended by airplane.

One minute later Voirin lifted the fuselage of the plane and slowly started to pick up speed when suddenly the load began to swing back and forth. The pilot opened the barycentric hook and the HB-ORP fell several hundred meters and smashed on the rocks.

The rescue operation thus ended in an "échec presque total", i.e. with an almost total disaster.

The appearance of the first turbine-powered helicopters such as the Bell UH-1 decreed the slow but inexorable decline of the so-called "first generation" helicopters. Heliswiss itself, in need of a helicopter with a greater load capacity than the Bell 47 series, turned its attention towards the Agusta-Bell 204B produced under license by the Italian company Agusta. That same year the first two (HB-XBN and HB-XBO) entered into service with the Belp/BE based helicopter operator.

In 1972 Heliswiss purchased the Sikorsky S-58T HB-XDT but the choice did not turn out to be particularly apt. Although more powerful than the S-58 this version did not live up to the expectations, and especially in mountain it soon showed its limits, but this is another story which deserves a separate chapter.

The last appearance of the S-58 in Switzerland dates back to the early 1970s when some German H-34s were taken to Belp/BE where, at least in the intentions, they should have been re-engined and transformed into S-58T. Apparently nothing happened, and nobody know where these helicopter were then transferred.

Did you know that...

The engine oil cooler (mounted at the front bottom), the engine and its components covered by the light clamshell doors as well as the high crew seats were particularly exposed to small arms fire and made the H-34 particularly vulnerable. For this reason, the French armed forces engaged in the conflict in Algeria added armoured protection. The Marines engaged in Vietnam also faced this problem.

In 1957 Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first US president to ride regularly on a helicopter. Initially he used a Bell OH-13J to reach his summer residence in Pennsylvania in a fast and comfortable way.

This quick and convenient way of getting around led to the development of a variant of the S-58 designated VH-34 with a VIP interior, improved instrumentation and navigation equipment, and emergency flotation devices. The helicopter designated "Marine One" when the president was aboard had a distinctive colour scheme that is still in use today and dates back to the time of the Eisenhower administration, when the aircraft did not have air conditioning. The top of the aircraft was painted white to reflect heat and reduce internal temperatures.

That’s why to this day, presidential helicopters continue to be referred as the "White Tops".

In September 1959 the Soviet Premier Nikita S. Chruščëv visited the United States where he had the opportunity to fly on one of the HUS-1 used for the transport of US President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The Cremlin chief's impressions were so favourable that he ordered two HUS-1s that were delivered in early December 1960.

On July 21, 1961, the space capsule Liberty Bell 7, after having passed through the Earth's atmosphere, landed in the Atlantic Ocean with the famous astronaut Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom on board. While waiting to be picked up by a Sikorsky HUS-1 Seahorse, for reasons never clarified, the hermetic door of the capsule suddenly opened, and the capsule began to fill with water. In the following minutes Lieutenant James L. Lewis tried desperately to airlift it out of the water and bring it to safety on the support ship. Despite his intrepid efforts he was forced to release the capsule that sank in the ocean with the precious data collected during the flight.

On July 21, 1999, exactly 38 years later, the capsule was finally recovered to be exhibited in a museum. However, the mystery of the sudden opening of the hatch was never clarified.

Videos

Check out these videos showing some Sikorsky S-58s in action:

Sikorsky S-58C startup, takeoff, pass, landing and shutdown

Brewster H-34 pattern

First S-58 flight

Sikorsky S-57/H-34, the sound of the 1960s

Acknowledgements

For the completion of this article I received valuable help from:

- Matthew Fraas, education specialist at the U.S. Army Transportation Museum, Fort Eustis, Virginia;

- Dan Libertino, President of Igor I. Sikorsky Historical Archives, Inc., Stratford, Connecticut;

- Rudolf Renggli, retired, for many years chief-mechanic at Heliswiss;

I would like to thank them for their kind support.

HAB 03/2022